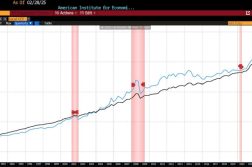

After disappointing readings in November, December, and January, inflation appears to be slowing once again. Could this mark the return to sustainably low price pressures?

The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased 0.2 percent in February, after rising 0.5 percent in January. The shelter index alone “rose 0.3 percent in February, accounting for nearly half of the monthly all items increase.” Prices are up 2.8 percent over the past year.

Core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, also rose 0.2 percent last month. They have risen 3.1 percent over the last year. After widening significantly in 2024:Q3, the gap between headline and core inflation is shrinking.

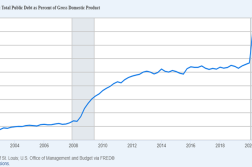

Both headline and core inflation have hovered around 3.0 percent annualized for more than a year. Let’s hope the new inflation data indicates reversion to the pre-covid trend, rather than fluctuations around a post-covid trend.

There’s a world of difference between 2.0 percent trend inflation and 3.0 percent trend inflation. It takes 35 years for prices to double at 2.0 percent, but only 23.3 years for prices to double at 3.0 percent. Investors with capital gains get pushed into higher tax brackets. And the Federal Reserve, which is supposed to keep price growth low and predictable, loses major credibility. To prevent this, central bankers should continue the push to 2.0 percent inflation.

Is monetary policy currently suitable to achieve the 2.0-percent goal? The Fed’s current target range for the federal funds rate is 4.25 to 4.50 percent. Adjusting for inflation using the latest headline CPI figures, the real rate range is 1.45 to 1.70 percent.

As always, we need to compare this to the natural rate of interest, which is the inflation-adjusted price of capital that balances short-term supply against short-term demand. The New York Fed’s estimates put this between 0.80 and 1.31 percent in Q4:2024. Since the lowest estimate for real interest rates in the market exceeds the New York Fed’s highest estimate for the real fed funds rate monetary policy appears to be tight.

Estimates of the natural rate vary, however. The Richmond Fed puts the natural rate of interest between 1.18 and 2.66 percent. That’s a wide range. That the median estimate of 1.89 exceeds the real federal funds rate target suggests monetary policy is loose. Hence, using interest rates to judge the current stance of policy depends crucially on one’s preferred estimate of the natural rate.

We should augment this analysis with money supply data. The M2 money supply is up 3.49 percent from a year ago. The Divisia aggregates, which are broader measures that weight money supply components by their liquidity, have risen between 3.26 and 3.53 percent over the same period. How does this money supply growth compare to money demand?

To proxy the demand to hold money, we can add the most recent real GDP growth and population growth figures. The Bureau of Economic Analysis says real GDP grew at an annual rate of 2.3 percent in Q4:2024. From the Census, we learn that annual population growth in July 2024, the latest data available, was about 1.0 percent. Hence money demand is growing roughly 3.3 percent per year.

So, the money supply is growing about as fast as money demand. Broadly, that suggests neutral policy. But neutral policy corresponds most closely to non-accelerating inflation. We still want price pressures to ease.

There’s no good reason to settle for 3.0 percent inflation. The evidence suggests that the Fed must tighten further to hit its 2.0-percent target. Whether it will tighten sufficiently or let inflation settle in above target remains to be seen.