In 2009-10, I was invited to dozens of speaking opportunities, as well as lots of radio and television appearances, because of my association with the “Tea Party.” Though now increasingly out of fashion, the informal moniker “Tea Party” referred to a loose confederation of citizens and political candidates who were concerned about the size of government, and especially about the federal debt.

In retrospect, it appears that all that energy (in the movement) and optimism (at least for me) was misplaced. As has been noted, regretfully or snidely, the stated purpose of reducing government spending has not only not been achieved, but has failed on a scale that is hard to imagine from the vantage point of the summer of 2009.

There is a fundamental problem of discipline, and incentives, in the political process of democracies. It has often been commented on, but appears to have no solution. The problem is that there are three considerations that, when taken together, force an impossible choice.

1. Voters say they don’t like government spending, but in fact they do, and will support candidates who increase government spending.

2. Voters say they want lower taxes, and in fact they do, and will support candidates who reduce taxes.

3. Voters say they want smaller annual fiscal deficits, and less overall debt, but in fact they don’t care at all, particularly if smaller deficits require reducing government spending (see #1) or higher taxes (see #2).

Since our elected officials aren’t official unless they are (re)elected, these three considerations suggest a potential for a corrupt bargain, and that’s just what has happened. Democrats have specialized in increasing government spending as a way to buy votes, and blame “low Republican taxes” for increased deficits. The Republicans have specialized in tax cuts as a way to buy votes, and blame “high Democrat spending” for increased deficits.

It is useful to establish some terminology.

A deficit is an annual shortfall of revenue, compared to spending. The difference is financed by borrowing, or “selling” US Treasury bonds. The reason investors are willing to buy bonds is that they are “discounted”: a $1,000 bond is sold at a price of $909.09; it will be worth $1,000 in a year, implying a 10% interest value, or rate of return. Treasury bonds are “auctioned” to ensure that the government pays the lowest rate to finance the deficit.

The opposite of a deficit is a surplus, where revenue exceeds spending.

Over time, the sum of the accumulated deficits and surpluses is the debt, or the total amount owed to bondholders.

Since mature bonds are constantly being retired, and new spending is constantly going out, the debt is always changing. In principle, if the old debt is being paid off by surpluses, which allow the debt to be retired, then the debt can shrink. But if there are consistent deficits, that maturing debt must be paid by selling new bonds. The problem is obvious: to pay the old bond, including the interest from the “discount,” the full amount must be borrowed. But then that amount must again be paid back, again plus interest, and so on.

There is another way to “pay” for deficits by issuing zero-interest bonds of a particular type: currency. The attraction of this method of financing is obvious, since no interest must be paid. The Federal Reserve Open Market Desk at the New York Fed need do nothing more than buy outstanding existing federal bonds, using newly “printed” dollars. (Of course, actual paper currency makes up less than 5 percent of the money supply, so these are really electronic rather than physical dollars.)

An overall increase in the price level caused by an expansion in the money supply, or the total amount of currency, is called inflation.

It’s easy to see why the “zero-coupon bonds” (dollars) are so attractive, from the perspective of politicians. If you sell actual bonds to finance the deficit, you have to pay interest. But if you just create new money and use it to buy bonds, then you ‘save’ twice: you pay no interest, and inflation reduces the real value of the debt to be repaid.

Of course, all of this was true in 2009 and 2010, when the push to reduce the debt was a key plank of Tea Party politics. The question is, what happened?

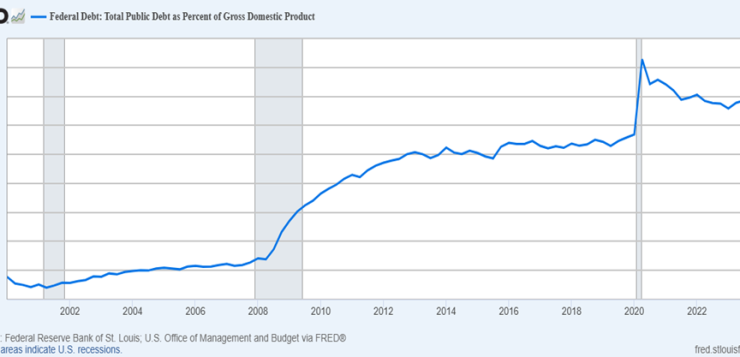

On the debt side, it’s pretty clear what happened: there was an orgy of deficits, accumulating a total debt that is nothing short of staggering. Expressed as a percent of US GDP, to account for scale, public debt went from less than 60 percent of GDP in 2000 to more than 120 percent of GDP in 2024.

Numbers this size seem cartoonish, but for context this works out to an unsecured obligation of well over $100,000 per man, woman, and child now alive in the US.

Fortunately, the current administration in Washington has promised to address the debt, or at least the rate of growth of the deficit. Less fortunately, this promise shows little prospect of being carried out. The current GOP budget, even if it is passed with no amendments or increases, actually increases the deficit, and will expand the debt by even more than the Biden budget inflated government borrowing in the previous year.

None of this is going to change until voters press members of Congress either to cut spending sharply, or to raise taxes. We are living far beyond our means, and — as I have argued before, back in 2009, when it seemed that people were listening — that is daft. Because Deficits Are Future Taxes (DAFT).